DEAL STRUCTURES

Partnerships may be described as front-loaded (the partner will pay more upfront and in near-term milestones) or back-loaded (less upfront but higher royalties down the road).

On one end of the spectrum, there are small companies trying to out-license preclinical candidates. A partner might pay, for example, $100K upfront upon signing such a deal, $500K in preclinical milestones, and then $500K, $1M, and $3M in milestones upon initiation of Phase I, initiation of Phase II, and FDA approval, respectively, with a 4% royalty on net sales. The tangible value to the struggling startup is small, little more than the sum of the first few payments ($1.1M). In exchange for shouldering much of the risk, the partner keeps most of the profits.

From the small company's perspective, engaging in the early-stage front-loaded deal described above is similar to doing contract research with little or no upside if the drug is ever successful. Most of the value of drug development is realized near the end of the process, when the risk of clinical failure has been mitigated with positive data. Therefore, if a biotech company wants to be more than a contract research organization (CRO), it must take on more risk than a CRO. It must develop its drug candidate into the later stages of human trials. With positive Phase III data, for example, the company may be able to negotiate a deal with generous upfront payments and a large share of the downstream profits.

On the other end of the spectrum, Millennium's 2003 Velcade deal with J&J is an example of a heavily backloaded arrangement. The deal was announced in June 2003, when the drug had just been approved in the US for treatment of multiple myeloma and was awaiting approval in Europe. Millennium gave up rights to Velcade outside of the US, keeping US marketing rights for itself. J&J only paid $15M upfront to Millennium but shouldered 40% of Velcade's further development costs in cancers and agreed to pay up to $500M in sales and development-based milestones as well as an estimated 20% royalty. Millennium kept all the revenues from US sales. With about $1.5B in the bank, Millennium could afford to forego upfront payments in exchange for retaining the lion's share of Velcade's economics.

The following sections describe in more detail some of the components and devices employed by companies to share expenses, revenues, and risk. Each may be incorporated in some fashion as a term or option in a corporate partnership.

UPFRONT FEES AND MILESTONE PAYMENTS

The company buying into the partnership will often make an initial cash payment and agree to make several additional payments contingent upon:

-

Successful completion of development milestones such as

i. Initiation of Phase III trial

ii. Submission of NDA

iii. FDA Approval of NDA

-

Achievement of sales thresholds (e.g. first $100M of sales, $250M sales)

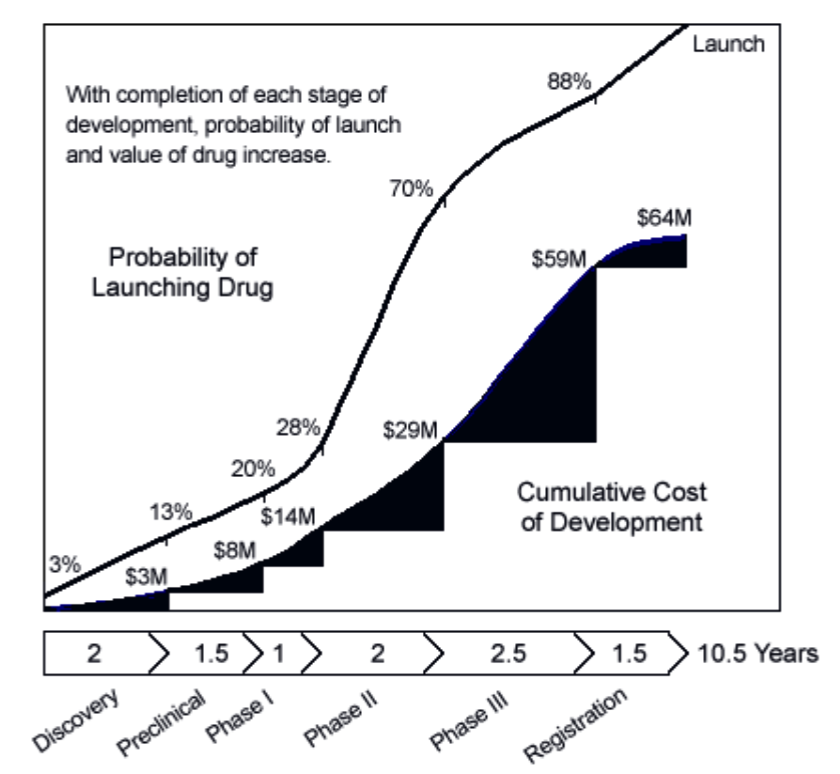

Depending on the product and stage of development, both the amount and timing of upfront and milestone payments may vary. A Phase I drug may only justify a $2M upfront and $20M in milestones, whereas the same program that already has Phase II data demonstrating the drug's efficacy might command five times more. The total value of the deal will depend on whether the partner will pay for future development costs, buy equity, and pay a royalty.

Figure 3. Drug Development. Probabilities are based on industry averages. Costs are typical of what small biotech company incur developing a since product.

R&D SPONSORSHIP

The costs of running an R&D program can be significant, and it helps to have a partner cover all or part of the expenses, which include the cost of in-house labor (measured in Full-Time-Equivalents or "FTEs" such that 2 half-time employees add up to 1 FTE) and out-sourcing expenses such as those associated with process and clinical development.

Some companies, eager for validation of their technology and a source of revenue, may too quickly agree to work for their "partners" in exchange for little more than having their expenses reimbursed -- such arrangements are profit neutral, not hurting but also not helping the bottom line. Companies that neglect to partake in the significant upside of drug sales may become little more than contract research organizations, covering their costs but not generating the levels of profit that justify a high valuation. It is important to consider that management's bandwidth (the number of tasks that can be managed at one time) is a limited and precious resource. Partnerships mostly involving research sponsorship, while profit neutral, may distract management from more ambitious goals.

A research sponsorship gives the company doing R&D little incentive to be more efficient since any cost savings are enjoyed by the paying partner. An alternative to counting FTEs is to negotiate for success-based milestones, which reward efficiency.

EQUITY INVESTMENTS AND LOANS

A new partner may make an equity investment in a smaller company as a form of payment. Usually, the valuation of the stock is inflated relative to what ordinary investors would pay for it since the new partner is getting more than just stock out of the deal.

Equity purchases are reported as investment on the balance sheet transaction instead of as cash expense on the income statement, which lower reported earnings. The partner usually will not acquire more than 19.9% of the total stock. If Company X owns 20% or more of loss-generating Company Y, an equal percentage of Y's losses would have to be included on X's income statement, thereby lowering X's reported earnings and hurting its stock price.

Loans are also a form of payment, particularly when they are interest-free, convertible to stock, or potentially forgivable (e.g. the partner will not require repayment of the loan if a particular milestone is met on time).

ROYALTIES

A royalty is a payment based on product sales. Royalties may be a flat percentage of sales or tiered, like US federal tax brackets. A tiered royalty, for example, might be structured as 10% on annual sales up to $100M, 12% on sales >$100M, and 14% on sales >$300M. Compared to marketing your own drug, one advantage of receiving sales-based royalties from a partner is that you get paid even when the drug is not yet generating profits. While royalty payments may be too far off to provide a startup with the cash flow it needs to grow, royalties are an effective means of generating significant value in the longterm and each percentage point is worth negotiating for.

Royalties are also larger than they seem. For example, a typical Phase II-stage deal may include a 10% royalty on worldwide sales, with the pharmaceutical company covering all future expenses. Therefore, when the drug is generating $500M/year, the pharmaceutical company will keep $450M and give $50M to its biotech partner. However, after manufacturing, sales, and other expenses, the pharmaceutical company may be left with only $250M, which would mean that the biotech company's 10% sales-based royalty represented 17% of profits ($50M out of $300M). To go a step further, a 30% royalty may have the same effect on a company's bottom line as a co-development profit-sharing deal in which both partners split revenues and expenses 50/50.

One rarely sees licensing arrangements in which the marketing company pays the developer a royalty in excess of 30%. This is because a royalty that is 30% of sales is roughly equal to half of the profits. Considering the huge effort and expense of marketing a drug, it would require very unusual circumstances for a pharmaceutical company to part with more than 50% of its profits from a drug. Theoretically, if clinical data suggested the product will be a blockbuster, a pharmaceutical company might still pay generously for less than 50% of the profits. Consider the BMS-Imclone deal for the cancer drug Erbitux.

In 2001, presumably after reviewing Phase III results, BMS agreed to pay for half of Erbitux's future development costs, bought $1B in Imclone stock at a 40% premium to its price on the open market, agreed to pay upfront and milestone payments totaling $1B and a 39% royalty on sales in N. America, and agreed to split profits 50/50 in Japan. With all these expenses, BMS is giving to Imclone more than half of the total profits from US and Japanese sales. Had Imclone partnered Erbitux at an earlier stage in development, the terms of the deal would have been far less generous to Imclone.

PROFIT-SHARING

A company developing a drug may agree to share in the ongoing development and commercialization costs of the drug, including the high costs associating with first launching a new product, in exchange for also proportionately sharing in the drug's profits. This means that both partners accept the risk that the drug might never be approved or become profitable. However, just because two companies enter into a profit-sharing arrangement does not mean that the company that discovered and partially developed the drug will not be paid upfront fees and milestones. In fact, these payments from the partner may be what allow the company to shoulder its share of the ongoing commercialization costs.

MANUFACTURING

FDA regulations concerning Good Manufacturing

Practices of drugs are very strict and a factory that fails an inspection may be promptly shut down, possibly resulting in product recall and millions of dollars in lost sales. Therefore, big pharmaceutical companies are generally hesitant to trust inexperienced biotech companies with manufacturing and will negotiate for this right during partnership discussions. Since manufacturing a drug is a step towards maturity and full integration, young company may try to retain the right to manufacture the drug and sell it at a slight markup to the marketing partner. For example, the Erbitux deal mentioned above had Imclone selling the bulk material to BMS at a 10% premium to Imclone's cost of manufacturing it.

CO-PROMOTION VS. CO-MARKETING

While often used interchangeably, there is a fundamental difference between co-promotion and co-marketing. If two companies agree to co-promote a drug, this usually means that both will deploy their sales forces collaboratively to sell a drug under a single brand name. When co-marketing, each will sell the drug under a different brand name, as if they were two entirely different drugs, and may avoid competing with each other by targeting different markets.

Co-marketing arrangements are rare, though a notable example concerns erythropoietin. Amgen sells this compound as Epogen in the US for the renal market. Amgen also licensed erythropoietin to J&J for sale as Procrit for all other indications (most notably cancer) in the US and for all indications outside the US. The drugs are identical; in fact, J&J buys its recombinant erythropoietin from Amgen. Squabbles arise whenever one appears to encroach on the other's territory, demonstrating how difficult co-marketing can be.

Co-promotion arrangements, on the other hand, are not uncommon and make sense if one company lacks the sales force to penetrate a market to which another company could sell effectively. For example, while a biotech company developing a drug for overactive bladder might build its own 100-person sales force to target the 12,000 urologists in the US who write 30% of the scripts, the same company would be hard-pressed to build a 3,000-person sales force to market this drug to the hundreds of thousands of primary care physicians (PCPs) who write the majority of OAB scripts. Therefore, the biotech company might partner with a pharmaceutical giant that could target PCPs while allowing the biotech company to co-promoting the drug to the smaller and more tractable urology market. Most importantly, the bigger partner will usually cover the costs of the smaller company hiring and maintaining its sales force.

A biotech company will often prefer a co-promotion agreement that involves sharing of sales revenue and expenses, essentially profit-sharing, rather than a royalty-paying deal. The contributions to the biotech company's bottom line may be the same in either case, but a co-promotion deal lets the biotech company report substantially more in top-line revenues. Booking top line sales of a drug product is considered more prestigious than merely collecting royalties- the former is indicative of a more mature company with sales/marketing capabilities.

However, not all co-promotion arrangements allow both partners to book sales to their respective top lines. In many cases, all sales are credited to the big partner, who then pays royalties to the smaller biotech company. The biotech company is paid equally whether it co-promotes the drug or just lets its partner handle all sales. However, by exercising its co-promotion option, the biotech company essentially gets a free sales force that can be leveraged to sell other drugs it develops or in-licenses. Therefore, a co-promotion deal can be a big step for a biotech company trying to mature into a fully-integrated pharmaceutical company.

JOINT VENTURES

Some deals between companies involve the creation of a third entity, often called a joint venture (JV), which may be nothing more than a paper company of which each partner owns a portion. The JV may be funded by one partner or both, have scientific and administrative staff from one partner or both, and may receive licenses to each of the partners' relevant technologies. For example, the larger partner may agree to pay for all the work being done by the JV. The JV may, in turn, make payments to the smaller partner for the use of its people, equipment, laboratory space, and intellectual property. At some point, the JV might agree to license a drug to the larger partner, which would pay royalties to the JV. Eventually, that money would find its way to the smaller partner. The JV is really an accounting construct which one or both partners may favor over a direct transaction because of how a JV affects their financial statements.

TERMINOLOGY: LICENSING DEALS, PARTNERSHIPS, & ALLIANCES

Arrangements in which a risk-averse company relinquishes development entirely to another company in exchange for payments are typically referred to as licensing deals. While most arrangements between drug companies will involve a license (transfer of rights from one partner to another), the terms partnership or alliance connotes both parties playing an important role in developing and commercializing a product. These terms are not rigidly defined and are often interchangeable.