BIOTECH PAST

Biotech's evolution is marked by fits of innovation. What started with a few scientists cloning proteins, transitioned to antibody development, high-throughput screening of small molecules, and, more recently, in-licensing drugs that were partially developed by other companies. At first companies tried to develop drugs on their own, but they would later actively seek larger partners with whom to share the risk and expense. The logic of these transitions is evident from a review of the sector's brief history.

THE EARLY DAYS

In the 1980s, biotech companies plucked what we now know to be relatively low hanging biotech fruit: recombinant secreted proteins such as insulin, erythropoietin, and interferon that replace what the body lacks. Developing therapeutic antibodies proved more challenging, but these products also started to be approved with some regularity in the late 1990s.

One out of an estimated 5000 discovery-stage drug candidates goes on to become an approved drug and only one-third of those drugs successfully recoup their R&D costs. Hundreds of companies no one ever talks about anymore failed where Amgen and Genentech succeeded, not necessarily because they were less competent but often because the products they pursued were unexpectedly intractable.

The fundamental problem with the make-your-own-drug model was its tolerance of the cost and duration of drug development; setbacks and expenses we now can better anticipate came as surprises back then. With investors and entrepreneurs thinking that each infusion of capital might just be the last before profitability, the difference between success and bankruptcy often depended on how long investors could stay optimistic. Considering how little was known about the perils of biotech product development, many of the companies in Table 1 (see below) may have been just a coin toss from failure.

Throughout the 1980s, big pharmaceutical companies were slow to realize the potential of biotechnology to create value. They had faith in their own R&D capabilities and were reticent to pay biotech companies for their technologies or drug candidates. With little opportunity to share risks and expenses with Big Pharma, biotech companies had to rely on investors. Eventually, Big Pharma began to buy into the biotech revolution through acquisitions and partnerships, giving biotech companies an alternative to commercializing drugs independently.

FROM PRODUCTS TO TOOLS

By the mid-1990s, a number of investors and entrepreneurs focused on developing "faster, better, cheaper" drug discovery tools. Rather than risk their own capital on the success or failure of a few drugs, tool companies offered Big Biotech and Big Pharma technology licenses and services in exchange for milestone and royalty payments.

The switch from drug to tool commercialization was a fundamental business model shift. Tool development cycles were shorter and less costly, suggesting that these companies would turn a profit more quickly. However, the low barriers to entry allowed a flood of competing companies to appear overnight. Some, like Millennium, took a broad approach to genomics-based drug discovery,

| Table 1. Top Ten Drugs by 2001 Sales. Based on similar table published by Decision Resources: http://www.dresources.com/nature/ntr_1102.pdf | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Trade name | GenericName | Indication | 2001 sales(US $m) | Company (R&D) | Approved |

| 1 | Epogen/Procrit/ Eprex | Epoetin-a | Anaemia | 5,588 | Amgen | Jun 1989/Dec 1990/ May 1995 |

| 2 | Intron A/PEG-Intron/ Rebetron | Interferon-a2b | Hepatitis C virus | 1,447 | Biogen/ICN/ Enzon | Jun 1986/Jan 2001/ Jun 1998 |

| 3 | Neupogen | Filgrastim | Neutropaenia | 1,300 | Kirin/Amgen | Feb 1991 |

| 4 | Humulin | Human insulin | Diabetes | 1,061 | Genentech | Oct 1982 |

| 5 | Avonex | Interferon-b1a | Multiple sclerosis | 972 | Biogen | May 1996 |

| 6 | Rituxan | Rituximab | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 819 | Genentech | Nov 1997 |

| 7 | Protropin/Nutropin/ Genotropin | Somatotropin | Growth disorders | 771 | Genentech | Oct 1985/Nov 1993/ Aug 1995 |

| 8 | Enbrel | Etanercept | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis | 762 | Amgen | Nov 1998 |

| 9 | Remicade | Infliximab | Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis | 721 | J&J/Centocor | Aug 1998 |

| 10 | Synagis | Palivizumab | Paediatric respiratory disease | 516 | MedImmune | Jun 1998 |

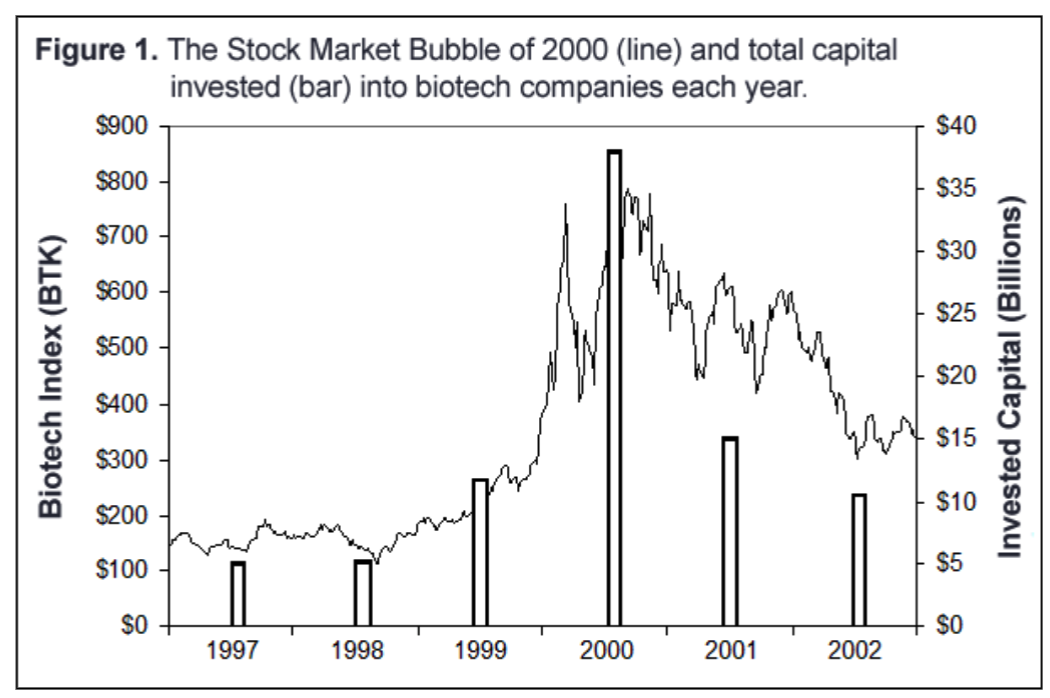

while many focused on one approach: yeast 2-hybrid screening, expression profiling, mouse knock-outs, etc. At first, big pharma paid handsomely to secure access to these technologies. For example, the total value of the deals Millennium signed from 1994-1998 with big pharmas such as Roche, Wyeth, Pfizer, Bayer, Lilly, and Pharmacia neared a billion dollars, though much of this value was locked away in long-term milestone payments. The frenzy over genomics and tool companies manifested itself as a surge in biotech stocks towards the end of 1999 and throughout 2000, as well as a dramatic increase in venture capital and public equity financing of biotech.

In 2001, a report by Lehman Brothers and McKinsey suggested that genomics-based drug candidates were more likely to fail in the clinic because they were not as well understood as candidates discovered by traditional means. The report pointed out that, on average, there were over 100 scientific publications discussing each non-genomic drug in clinical development, compared to only 12 publications about each genomic drug and its mechanism. The implication was that, at least in the near-term, genomics would make drug development less efficient, not more. Needless to say, investors were unsettled.

To make matters worse, the proliferation of similar technologies resulted in oversupply of drug discovery tools. Drug targets and preclinical drug candidates, became commodities. Most companies could not command the high prices for their services that they needed to meet financial projections. Unable to offset high expense, they had to raise more money, frustrating investors who had expected tool companies to reach breakeven quickly. It seemed there was no way to build a biotech company efficiently.

BACK TO PRODUCTS

Enthusiasm for tool companies declined (See Figure 1). Big Pharma stopped doing hundred-million dollar genomics deals and terminated many relationships. Investors cut back funding for tool companies. The collapse of the biotech market, led by the stark devaluation of tool companies, marked the industry's realization that a small company trying to capture the value of a drug had to do most of the development itself. Tired of betting on long-shots in an industry already fraught with risk, drug companies and investors focused their attention on less risky drug candidates closer to FDA approval and sales; in 2003 and 2004, product repositioning, finding a new use for an old drug (discussed below), came into fashion.

Many biotech companies in-licensed or acquired drugs, often from Big Pharma. Exelixis, which initially developed animal model systems for functional genomics, licensed the cancer drug Rebeccamycin, already in clinical trials, from Bristol Myers Squibb. Genomics giant Millennium, always a step ahead of the trends, used its stock while it was still highly priced as currency to buy Leukocyte and Cor Therapeutics, acquiring two FDAapproved drugs and a pipeline in the process. Ironically, many of the drug candidates in-licensed by cutting-edge biotech companies had been discovered using oldfashioned methods.

LESSONS LEARNED?

Being successful in biotech, as with any business, is about creating value, and the means are secondary. The biotech product with the highest value is and always has been the successfully marketed drug; profit margins for pharmaceuticals are among the highest of any business. The less a company is involved with actually marketing a drug (for example, by focusing on drug discovery), the less value it creates. Science and technology count for little unless they help make a better drug more efficiently, saving time and money.